Why do military coups d’état keep happening in Africa?

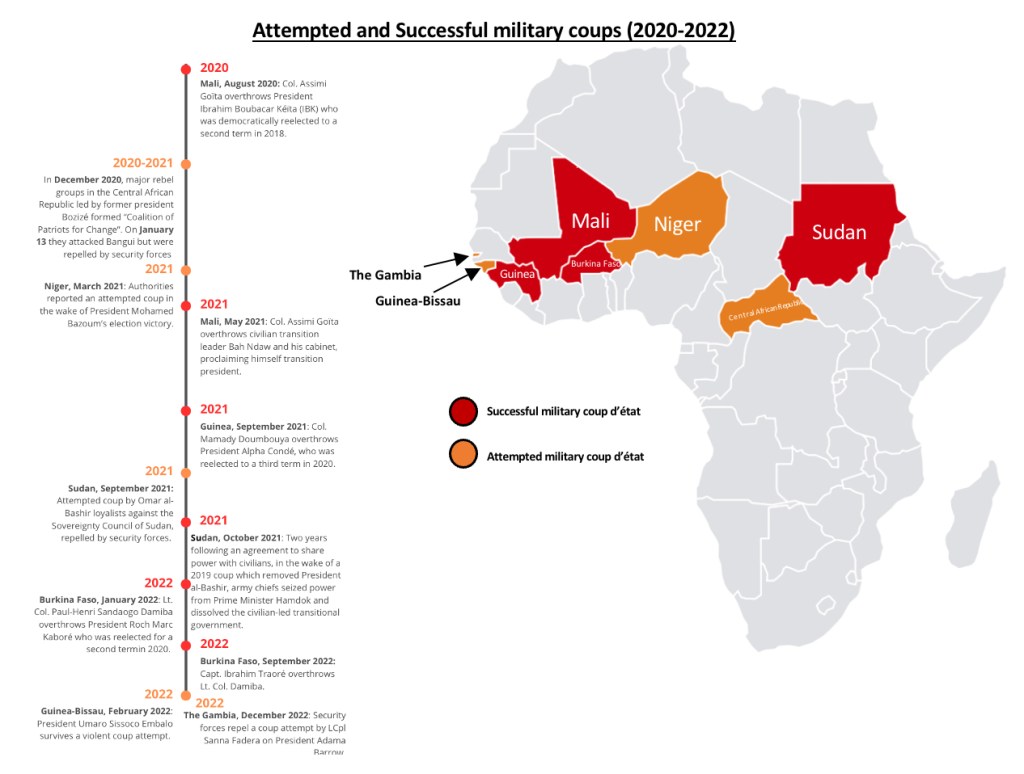

The period since 2020 to present has been eventful in Africa, not least because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but also due to the resurgence of successful military coups that have once again become the norm. Overall, since the beginning of 2020, six successful coups d’état conducted by active members of the military against a civilian government have been recorded in Mali (twice), Guinea, Sudan, and Burkina Faso (twice). In all of these military coups, the same modus operandi can be observed: 1) A faction of the military seizes communication centres and government buildings, detaining the president and the ministerial cabinet; 2) Coup plotters use the national radio station to broadcast to the nation, explaining how the civilian government’s corruption and ineptitude has made it a patriotic requirement for the military to intervene and seize power and 3) The coup plotters promise to return to their barrack and bring about a transition to a democratic system of government as soon as a just and disciplined society has been restored.

© Francky Ayosso

In every democracy, civil society and the military regularly interact, including in government. However, democratic rules require that military institutions remain neutral and subordinate to a civilian leader. This is because in every state, authority can be derived from legitimacy (i.e. elections) and/or coercion (i.e. violence). The electoral process involves a competition between civilians for political power whereas coercion is usually enforced by the military and the police. Therefore, in a democracy, where government is led by a civilian head of state, the latter derives his/her authority from legitimacy, whereby civil society voluntarily defers to the state through the electoral process, and from coercion but through the use of the military and the police. The military and police as an agency of coercion can be used by the state to force citizens to obey rules, either existing or established by political power, but also to accept a certain political order.

However, in Africa, the military has not always remained subservient to civilian government, leading to the multitude of coups d’état observed since 1952 when the first coup was recorded in Egypt. In total, 71 military coups d’état have been recorded in 60 percent of African states between 1952 and 1990, with countries such as Benin, Burkina Faso, Sudan, Ghana and Nigeria regularly being most frequently subjected to coups and countercoups during that period. In addition, these coups have commonly occurred during a period of crisis in which the legitimacy of an incumbent civilian government to exercise political power is in decline or lost, creating a period of instability and prompting different interest groups to compete with the failing elite, and each other, in order to establish a new political order. In this instance of instability and confusion, the military may seize power for itself or one of its political ally. However, it has proven hard to categorise coups precisely because every military coup d’état is different, affecting all forms of government (democracies, personal rule, or even an incumbent military administration), are a consequence of different motives (nationalism, selfish desire, or ideological), and result in different types of rules (autocratic/democratic, liberal/socialist etc). Nonetheless, attempts by political scientists have led to three broad categories for the typology of military coups:

The ‘guardian coup’ : Under this type of coup, the military intervenes in order to rescue the state from mismanagement, in the form of corruption and inefficiency, attributed to the ousted civilian government. Men in uniform essentially consider it a matter of national interest (thus nationalism) to intervene in order to preserve the nation from the incompetency of a civilian government. In many cases, following this type of coup, the military promise to (and eventually do) return to their barracks once discipline has satisfactorily been restored in the political process. On the other hand, the state of society and the economy is usually left unchanged following the transition to civilian government. Nigeria is a typical country that has experienced several (5) guardian coups since independence until the restoration of multi-party democracy and the return to civilian rule in February 1999.

The ‘veto coup’: A military coup can be categorised as such when the military intervenes in order to prevent changes that directly threaten its interests or that of its allies (selfish desire). This type of coup has, for example, been prominent in 20th century Central and South America where the military directly intervened to prevent leftist movements from seizing state power. In Africa, coups in 1992 and 2013 in Algeria and Egypt, respectively, can be categorised as veto coups as the military intervened, halting the democratic process and seizing power for itself, fearing that the outcome of elections might result in Islamist movements seizing political power.

The ‘breakthrough coup’: In this category of coup, the military intervenes to bring about a revolution by ousting an outdated (authoritarian/traditional) regime, leading to a complete societal change. The most emblematic example of a breakthrough coup is The 1974 coup in Ethiopia, where the military and its allied movements overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie’s 44-year traditional rule, and establishing a socialist state in its wake.

Beyond this simple typology of coups, there are two main, non-mutually exclusive, schools of thought that attempt to explain why the military coups materialise. On one hand, the ‘environmentalists’ school of thought, through Samuel Huntington and Samuel E. Finer, argue that coups d’état is likely to occur in a state that lacks an institutionalised political culture, and is suffering from economic hardship as well as social division. On the other hand, The second school of thought highlights the organisational ability and character of the military itself. In particular, Morris Janowitz and other academics argue that organisational cohesion coupled with core values of the military (patriotism, discipline, and professionalism) eventually lead the military to intervene and oust an incompetent and corrupt government. The two schools of thought are not mutually exclusive in the sense that bad socio-political conditions (first school of thought) likely creates the ideal conditions that require intervention from a well organised and morally motivated group (second school of thought) to intervene: thus the military. In that sense, the overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah’s regime by the military and police in 1966 is a good example. The decline in cocoa prices in the mid 1960s created enough economic hardship and social division to justify an intervention by the armed forces, leading to Nkrumah being deposed and replaced by a National Liberation Council (1966-1969).

Unlike western democracies, Africa typically lacks channels of non-violent political renewal which may be used to resolve political crises. General elections, the formation of a coalition government, or even referrals to a high court are virtually unimaginable in Africa’s current political context. This inevitably means that violence becomes a defining mechanism for regime change, and the military and police as the custodian of violence with access to the means to establish order is, unsurprisingly, likely to intervene.

Leave a comment